Can Joy Be a Worthy Muse?

A reflection on creation, suffering, and the myth of the tortured artist

As I begin my exploration of some of the greats, like Virginia Woolf, Ernest Hemingway, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, and Kafka, I’m struck by how often their pain, suffering, or addictions are framed as the source of their brilliance. After reading pieces of their work, and watching or reading others’ reflections, whether through essays, documentaries, and passing references, I’ve noticed a pattern. It’s not always the artists themselves who claim this connection, but the narration, the structure, the way we’ve come to tell their stories. It’s as if their anguish is a necessary rite of passage, a sacred offering that gave birth to their art. But should we see it that way?

Consider Dostoyevsky. Many of his greatest works were deeply reflective of his own life. In Crime and Punishment, the psychological torment of Raskolnikov mirrors Dostoyevsky’s own grappling with morality, guilt, and faith. He was imprisoned in Siberia for years after being sentenced to death for political dissent. That experience profoundly shaped his worldview and writing. The line between author and character often blurs, which makes his pain feel inseparable from his pages.

Then there’s Hemingway. So often, it’s his pain that gets told first: his alcoholic father, his overbearing mother, the war, the drinking, the depression. We speak of him through these lenses as if the man and the myth must suffer for us to admire him. But what would we know of him if we weren’t so fixed on this belief that great art must be born from great pain? What would we remember if we believed art could just as powerfully come from pleasure, from presence, from a sense of fullness rather than fracture?

In The Creative Act, Rick Rubin offers a different lens. He writes, “To be an artist is to be a conduit. In some moments, we may be moved to create from joy, in others from sorrow or confusion. The source does not matter. What matters is making something.” He suggests pain isn't a requirement for creation. In fact, he encourages artists to choose the more sustainable path when possible: “If you can choose between creating through joy or suffering, why not choose joy?”

That makes me wonder: do all artists truly have that choice? Or are some of us wired to reach into our own wreckage, not because we want to, but because it’s the only place the truth feels real? And if we, the audience, keep returning to their pain as the wellspring of their work, do we also trap them there? Are artists not only seen as shaped by their pain, but silently expected to keep experiencing it for us? To keep transforming it into something not just tolerable, but beautiful?

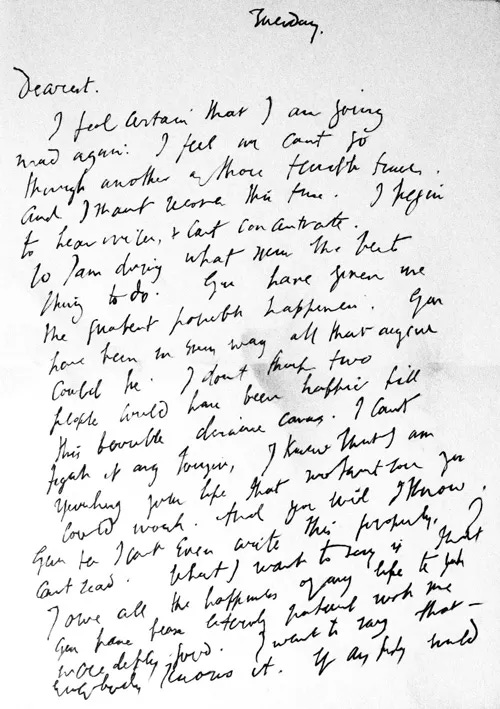

Take Virginia Woolf. Her final letter to her husband Leonard was never meant for public eyes, but it’s become part of her mythology. “I feel certain I am going mad again,” she writes, followed by a devastating farewell and a quiet praise of his kindness. “Everything has gone from me but the certainty of your goodness.” It’s a deeply personal moment, but like so much of her life, it has been absorbed into the story we tell of her artistry. Something meant for the two of them was spun into a symbol of her creative mind, her fragility, and her genius.

Kafka, too, never intended for his unpublished work to be seen. He asked for his manuscripts to be destroyed after his death, but his friend ignored that wish. Now, his raw inner world is taught, dissected, quoted, and praised. This makes me wonder even more deeply: are we selfish in the way we consume the pain of artists? In our desire for beauty and meaning, do we expect them to feel for us, to live and relive their suffering just so we can call it profound? Do we ask them, in some unspoken way, to turn agony into something we can understand?

Maybe that’s what we do with all great artists. We take the intimate and make it public. We make it art. But at what cost?

I don’t completely disagree with turning pain into art. Much of my own work has come from places of deep hurt, because those are often the moments that demand to be shaped into something. But what if it didn’t always have to be that way?

There’s a long history of romanticizing the suffering artist. We canonize their brilliance, often entwining it with their downfall, as if their work and their wounds are inseparable. But maybe we should begin to question that narrative. What if we chose joy when we could? What if we believed that pleasure, too, could hold meaning, and that wholeness could be just as compelling as brokenness?

Maybe I know less about these artists than I should to be asking these questions. But the wondering still feels worth something. So I’ll leave you with this: what might art look like if it didn’t always come from pain? If, instead, we sometimes allowed joy to be the starting point.